Learning objectives

|

Introduction

Aphasia is the most common early cognitive deficit after stroke, found in 20%-38% of patients. Speech and particularly language is an integral part of what makes us human. The loss of speech following a stroke can often be devastating. Almost a third of stroke patients develop difficulty with language. Persisting Aphasia/Dysphasia in particular affects mood, future employment and the difficulty in being able to make use of any medium that is language based. It is important that language issues are identified early and given appropriate therapy. Aphasia can have a serious impact on the communication aspects of patients’ lives and on their carers and it is important to ensure that families and carers understand how to support the patient.

Background

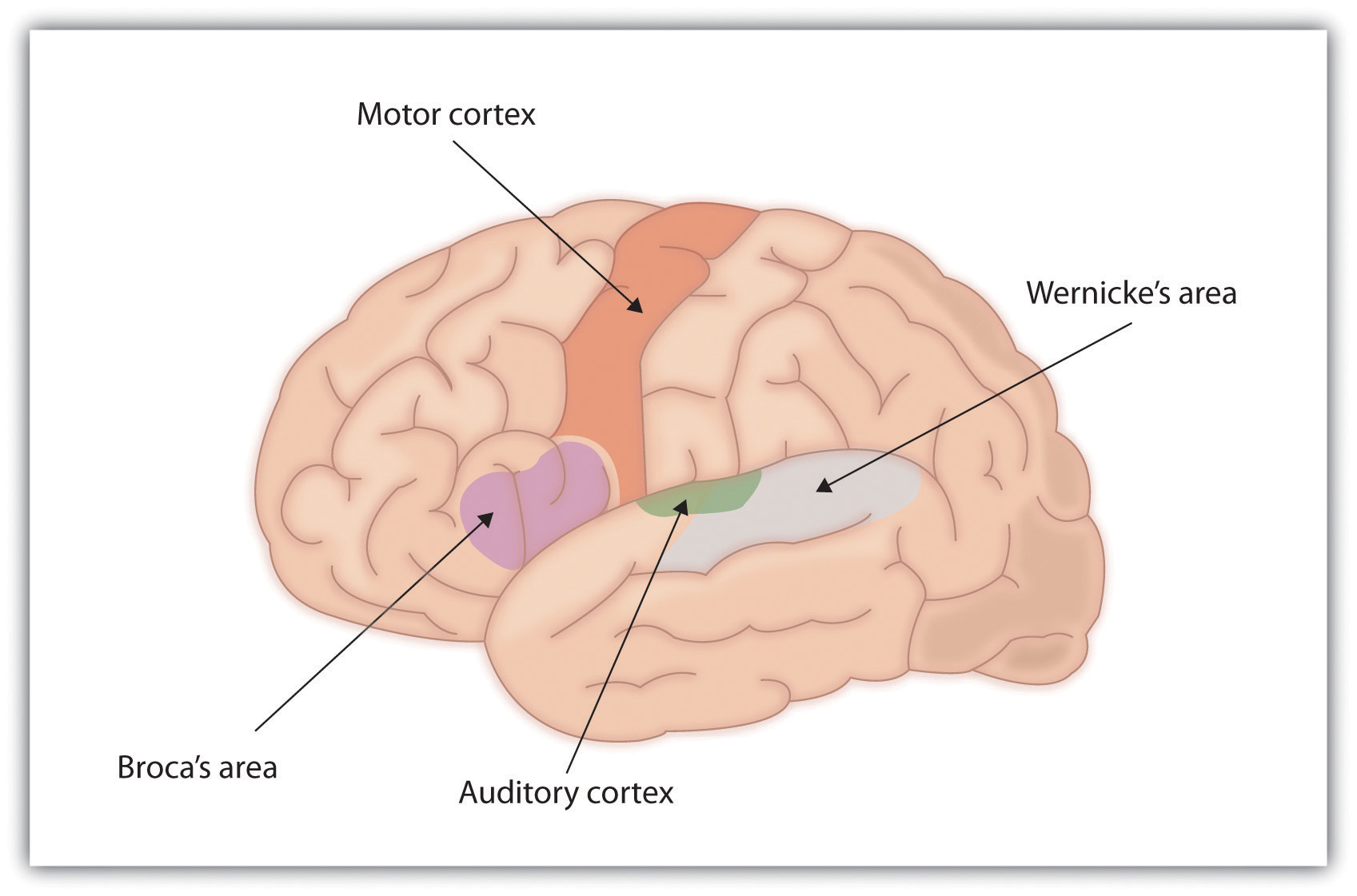

Difficulties with speech can be broadly grouped into difficulties with articulation and difficulties with the content of language. Language is a very localising neurology to the dominant cerebral cortex involving the dominant frontal lobe (Broca's area) the temporal /parietal lobe (Wernicke's area). It is a key symptom to recognise in stroke most commonly as part of a left MCA arterial syndrome. Dysarthria is far less localising and can be non-specific. Language issues can affect speech, oral comprehension, reading, and writing. For those interested in language then I highly recommend the Language instinct by Stephen Pinker to get some basic understanding of language and such fascinating issues in the understanding of language production.

| Terminology |

|---|

|

Aetiology

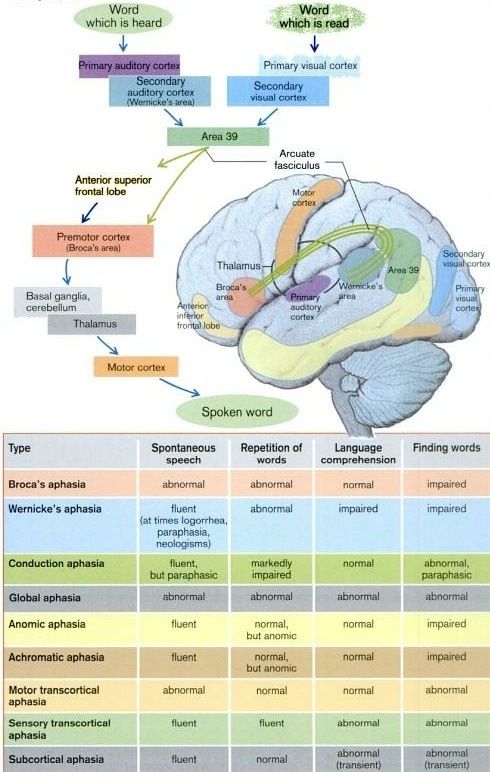

Traditional neurolinguistic models involve classical brain areas involved in language. This has generally included structures in the left cerebral hemisphere known as Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and the bundle of fibres connecting the two structures, the arcuate fasciculus. More recent studies indicate that the recognition of speech sounds is carried out in the superior temporal lobe bilaterally which is also involved in phonological-level aspects of this process. The frontal/motor system is not central to speech recognition but may modulate auditory perception of speech, that conceptual access mechanisms are likely located in the lateral posterior temporal lobe (middle and inferior temporal gyri). Speech production involves sensory-related systems in the posterior superior temporal lobe in the left hemisphere, that the interface between perceptual and motor systems is supported by a sensory-motor circuit for vocal tract actions (not dedicated to speech) that is very similar to sensory-motor circuits found in primate parietal lobe. Verbal short-term memory can be understood as an emergent property of this sensory-motor circuit. There is a dual stream model of speech processing in which one pathway supports speech comprehension and the other supports sensory-motor integration. Damage to these areas and the underlying neural networks has been felt to be responsible for specific language deficits, or aphasias. Models based on this with a clinical-pathological basis have helped. Newer neuroimaging may suggest that this model does not fully explain the language impairment seen but traditional models serve us for now.

Key Anatomical structures

Paths involved in repeating a read or heard word

Key questions for examining speech

Distinguish it from other related conditions

- Motor speech disorders

- Cognitive-communication disorders

Definition of aphasia

Disturbance of language caused by brain damage affecting:

- Comprehension : Auditory and/or Reading

- Expression: Speaking, Writing, Signing

Important distinctions to determine by assessment

- Language: Vocabulary, grammar

- Speech: Movement, tongue, lips…

- Cognition: attention, memory, problem solving

Language Input: How the Brain processes the Comprehension of Speech

- Auditory Language Hearing: Ears to Auditory Cortices to Wernicke’area

- Visual Language Reading: Eyes to Visual Cortices to Wernicke’s area

- Constructs an overall meaning and assigns meaning to words/relation among words

- Evaluates the context (literal vs figurative meaning)

Language Output: Spontaneous Spoken Language

- Wernicke’s area retrieves words, sentence structure

- Arcuate fasciculus transmits it to

- Broca's area formulates an action plan

- Sends plan to primary motor cortex which refines it

- Sends to the cranial nerves for speech muscles via bulbar nuclei

Repetition (tests the entire language circuit)

- Primary auditory cortex speech/Visual cortex for reading

- Wernicke's area

- Arcuate fasciculus

- Broca's area forms articulatory plan

- Primary motor cortex

- Pyramidal system to CNs for articulation or to arm for writing

Bedside assessment

- Initial introductions will give some clue as to a language issue.

- Patient may have no speech at all and may be mute due to severe dysphasia or dysarthria.

If they can speak then assess fluency and volume as you recount the history - Assess Comprehension of language: you may try and ask the patient to execute a 3-step non-verbal task, e.g. 'touch your chin, then your nose, then your ear'. It is important that you give no visual clues and the instructions communicated only through the content of your speech. If the patient fails, then try a simpler command down to the simplest which will usually be a midline command e.g. touch your nose or open and close eyes. This is useful for differentiating delirium and dysphasia. Even the most confused patient can follow basic commands and understands language.

- Test articulation: Repetition: 'no ifs, ands or buts' and 'British constitution'

- Naming objects: point to 2 objects e.g. a pen and a watch are commonly used

| The evaluation of a patient with suspected motor speech disorder should also include assessment of hearing |

Assessment of Speech

- To begin, say to the patient: 'tell me where you are? or 'describe x for me'.

- This will get them talking and enable you to screen for any abnormalities.

- Is the patient confabulating? (making up content to compensate for anterograde amnesia - seen in alcoholics with Wernicke-Korsakoff's phenomenon).

- Ask the patient to repeat the words: 'British constitution' and listen for dysarthria

- Get the patient to perform 3-step commands see below (any receptive dysphasia?)

- Test for nominal aphasia: Name a watch, pen, belt, tie, watch hands. Ask what these objects do (nominal aphasia/expressive dysphasia)

- Cough + say ?eee? (dysphonia)

- Word finding: Say as many words beginning with S in 1 minute (< 12 abnormal)

- If appropriate, perform a Mental State Examination but this will be impaired if there is abnormal speech which can give a false assessment of cognition

Commands

- 1 stage: open your mouth

- 2 stage: with your right hand touch your nose

- 3 stage: with your right hand touch your nose and then your ear

Abnormalities

- Dysphonia: altered volume and inappropriately quiet speech due to ENT disease or functional. A bovine cough suggests RLN nerve palsy.

- Dysarthria: inarticulate speech. Slurred and slowed pronunciation on saying "British constitution"

- Dysphasia (receptive): difficulty in understanding speech. Assessment: Execute a 3-step command. Often have fluent speech.

- Dysphasia (expressive): can understand but cannot answer appropriately. Assessment: Non-fluent speech, word finding difficulties

- Dyspraxia: The person knows what to say but has difficulty controlling the complex motor skills around speaking

Aphasia/Dysphasia

Aphasia is an impairment of language, affecting the production or comprehension of speech and the ability both to read or write. Aphasia can be used interchangeably with dysphasia but aphasia usually suggests a more severe form. Aphasia is a bit like being alone on holiday in a land where you do not know the language and can neither understand it, speak it or read it. You will understand gestures and mimicry and facial expressions and any form of communication which is not language dependent. Dysphasic patients will often nod to get you to produce more speech in the hope that they will understand something. It becomes extremely distressing as the patient has no one to relate to. When they watch TV its a bit like a foreign film only there are no subtitles that will help a dysphasic patient.

| Speech Problem | Explanation |

|---|---|

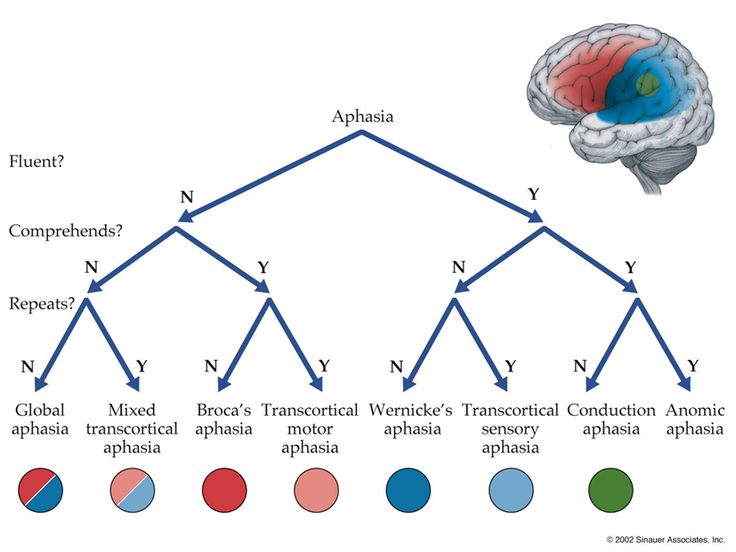

| Global aphasia | is loss of all three - Broca's, the arcuate fasciculus and Wernicke's areas, resulting in a total language disturbance. This is the most severe form of aphasia and is applied to patients who can produce few recognizable words and understand little or no spoken language. They can neither read nor write. |

| Broca's (expressive/non-fluent aphasia) | Difficulty in expression of speech and speech output is severely reduced is limited mainly to short utterances of less than four words. Caused by a lesion in at the inferior frontal gyrus (on language dominant hemisphere). Vocabulary access is limited and the formation of sounds by persons with Broca's aphasia is often laborious and clumsy. The person may understand speech and even be able to read but is limited in writing. Speech is slow and forced and halting and difficult. |

| Mixed non-fluent aphasia | Both Broca's and Wernicke's areas are damaged, leaving little comprehension/expression of language, however repetition is possible. Speech is sparse and effortful speech, resembling severe Broca's aphasia. However, unlike persons with Broca's aphasia, they remain limited in their comprehension of speech and do not read or write beyond an elementary level. |

| Wernicke's (receptive/fluent aphasia) | Difficulty in comprehension with an inability to grasp the meaning of spoken words is chiefly impaired. Caused by a lesion in at the posterior part of superior temporal gyrus (on language dominant hemisphere). Speech may appear quite fluent but may not make sense. Repetition of language is usually impaired. Sentences do not hang together and irrelevant words intrude-sometimes to the point of jargon. Reading and writing are often severely impaired. |

| Anomic aphasia | Person cannot supply the words for the very things they want to talk about-particularly the significant nouns and verbs. Speech is fluent and grammatical but there are vague circumlocutions and expressions of frustration. They understand speech well, and in most cases, read adequately. Difficulty finding words is as evident in writing as in speech. |

Dyspraxic Speech

Apraxia of speech is seen when a patient has trouble saying what he or she wants to say correctly and consistently. Speech is often very slow, deliberate, effortful speech. Their may be impaired prosody. It is not caused by weakness or paralysis of the speech muscles or aphasia though these can coexist. It is simply a difficulty in the motor skills of the action of speaking and inability to control and synchronise the movements necessary for speech. Apraxia of speech strongly associates with lesions of the left inferior frontal gyrus and the left anterior insular. Diagnosis and management involve one-on-one speech-language therapy sessions.

Prognosis

Many patients experience spontaneous recovery in the first two weeks after stroke. Most return is within the first three months, after which recovery is slow. Women recover better than men in oral production and auditory perception. A higher IQ a higher level of education increase the recovery of speech. Speech recovery may be better and faster in left-handed and ambidexter patients. Early and intensive therapy is needed.

Management

- Dysphasia is distressing. When talking to a patient with dysphasia first take your time. Smile and use non language forms of communication such as gestures, pictures, drawings, diagrams and mimicry. Say one thing at a time slowly and use short sentences. Don't pretend to understand if you don't. Relax and allow patient to relax. Exclude background noise and distractions. Recap and ensure that you haven't misunderstood.

- Early recognition is key and involvement of Speech and language therapy who have the time and skills to focus on speech and language issues. Exposure to language is useful. Having a fluent partner to encourage and increase exposure to speech.

- It is important to explain the disorder to carers and family and usually use the thought experiment that they wake up in a foreign hospital not speaking or understanding a word of the local language and how they would feel and cope. Important to explain it is not a cognitive issue that the person still recognises family and friends and has interests.

- The evidence shows that communication therapy was most effective in the first 4 months and had no added benefit beyond that from everyday communication after the first four months after stroke.

Links and References

- Basics of speech neuroscience

- National aphasia association

- Effectiveness of enhanced communication therapy in the first four months after stroke for aphasia and dysarthria: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;345:e4407

Note: The plan is to keep the website free through donations and advertisers that do not present any conflicts of interest. I am keen to advertise courses and conferences. If you have found the site useful or have any constructive comments please write to me at drokane (at) gmail.com. I keep a list of patrons to whom I am indebted who have contributed. If you would like to advertise a course or conference then please contact me directly for costs and to discuss a sponsored link from this site.